Artificial Intelligence and the Climate Crisis - How AI powered probabilistic thinking potentially solves a wide range of societal problems related to our ongoing interactions with the climate.

KRISCON / 2024

Authored by: Jesper Bork Petersen and Mads Prange Kristiansen

Executive Summary

AI powered probabilistic thinking potentially solves a wide range of societal problems related to our ongoing interactions with the climate. We can expect to see far-reaching innovations within crop-development, mining prospecting, material efficiency within solar etc. On the face of it, technical advancement takes us ever closer to a world potentially defined as post-scarcity.

Climate action, however, relies on more than just technology. Key constraints to getting to an equitable and sustainable path are a) political: the climate has a global scope, while our democratic scope remains largely national. b) psychological: to what extent do we simply swap gains in efficiency to increases in consumption? c) economical: nothing in the present suggests that the distribution of income connected to AI should be anything other than unequal.

We need to price in externalities. AI, on its present path, will unlock value and potential, open doors we hadn’t thought possible, but there will likely be consequences and adverse side-effects as well. The extent to which the negative externalities impact the constraints will be critical.

Background

The motivation for the article comes from an assignment KRISCON did for a Private Equity firm in Austin, Texas, which asked us to discuss “AI application in geospatial planning for photovoltaic”. This discussion quickly curve-balled into an existential scope, one that we thought interesting enough to pursue over a set of internal company conversations and, ultimately, transcribe in edited form onto the written form. No Large Language Models /LLMs) or other AI tools we used to construct this article.

Introduction

In the face of escalating climate change, the quest for sustainable solutions is ever present. As we grapple with the existential threat, the role of technology, including Artificial Intelligence (AI), in mitigating climate change has become a topic of intense interest and debate.

Below we attempt to shed light onto the intricate relationship between AI and climate change, exploring the applications of AI in addressing this global crisis. But even more so, we take a first attempt at some of the philosophical and ethical questions AI applications raise. We dive into the role of human psychology in achieving a sustainable future and the possibility of compensating for it with AI. We discuss the concept of valuing the future against the present and its implications for decision-making.

The starting point in much of the public debate often focuses on the extent to which we might leverage AI to massively reduce our carbon footprint, thereby achieving sustainability. Implicit in this thinking is that we are dealing somehow exclusively with a technical problem, or at the very least one that can be solved by technology. With the right energy-mix, we can quickly be on a sustainable path. But is this how we ought to think about sustainability, or should we really be concerned with the more complex matter of human behavior and choices, and defined thus, is sustainability ultimately beyond the reach of technology?

Does Industry 5.0 bring with it a post-scarcity Society?

Having completed four industrial “revolutions” already, we stand at the cusp of the next big societal change, what’s colloquially known as Industry 5.0. The first three revolutions occurred with large - albeit progressively smaller - intervals but the Internet-of-Things and the AI revolution we are about to embark on have come about in quick succession. From the mid-18. century onwards humans and animals alike began to be replaced by steam engines, as energy-exploiting technology competed with and augmented expensive labor. Industry 2.0 saw us scaling manufacturing and production in the 1870’s. Industry 3.0 occurred in the 1960’s, as a major overhaul of the productive capabilities saw the introduction of IT and automation. Industry 4.0 brought us wireless connected devices, cloud services, machine learning and AI emergence. The physical and digital capabilities of our race started to morph.

What if Industry 5.0 is when we finally have the toolkit to achieve genuine sustainable growth? Say that Sam Altman’s predictions, that the marginal cost of energy goes to near zero, as AI-enabled research into renewable & nuclear, come to fruition. Let’s assume – for the sake of argument – that AI does indeed enable us to drive up efficiency in our energy production, whilst also minimizing costs (the conventional ones, as well as the hither-to-difficulty-to-contain negative environmental externalities) and achieving sufficient carbon storage. What would this world look like?

In this future, with technological innovations driving energy costs to zero, we’ve all theoretically become rich. But isn’t that what has happened today in relation to 250 years ago. Relative to then, aren’t we already rich? It’s hard to argue that we aren’t. And yet, the societal outcome anno 2024 is quite far from anyone’s desired a priori vision. Wealth increases have created inequality and a cutthroat status-driven urge to self-realize. The creative class could well pull the plug and make art for pastime, but we’ve decided, collectively, as human beings, that we absolutely do not want to do this. We instead differentiate ourselves by way of excessive consumption of goods. It seems we have reason to fear that climate-positive-efficiency-gains are swiftly matched by equal increases in climate-negative consumption. I.e. that for instance increased efficiency in self-driving cars is met 1-to-1 or more by an increased demand for transport, the result being net increases in emissions.

So, if AI-enabled wealth alone won’t take us to sustainability, can we instead envision a desired state of nature to then use AI to extrapolate backwards? Is that how we transcend the ego that pursues power and profit at the expense of the eco-system? Is that our way out of a human condition which weaponizes our greatest inventions in the pursuit of unsustainable profits?

Does AI allow us to reverse-engineer the future?

Envisioning the future is an integral part of mitigating climate change, however else will we be able to set and keep course? For this article we use a conception of the future that we utilized while developing a cellulose-based construction material intended for low-cost housing. It entails a mental picture of us living with nature, in nature as nature. A planet-wide eco-system where we are close to our communities, where we have time and capacity to care for our choice of materials, where biophilic design is standard. Power is free, and by extension there is sufficient food for all. Efficiency has long since exceeded our basic and advanced human needs and desires, giving us the gift of creative work that offers enthusiasm and a higher level of consciousness. In this future, we are not just surviving, but thriving, co-existing, peacefully.

To simplify, this future vision is a representation of the exact point in time when the tech. advances from the industrial revolutions uphold and safeguard a perfect equilibrium in the eco-system, including us humans. Where resource consumption is balanced with regeneration and advancements in technology are no longer a requirement for our survival, but a sharpening of our tools to maintain it. Could we use AI to work backwards and create a roadmap to get there, and then continue to steer us as we progress towards it?

AI, with its ability to process vast amounts of data and identify complex patterns, could potentially help us chart the course to this future. It could analyze various factors, from resource consumption to social dynamics, and propose strategies to achieve our vision. It quickly becomes clear that not all 8 billion people on our planet will desire our vision. We would need a structure to create a consensus, and unless we want to run into a true ‘chicken and egg’ scenario and a democratic nightmare we cannot afford to wait for, we will also want AI to define this for us. If not, we find ourselves confronting the fundamental collective action dilemma, with a high probability of encountering the identical challenges associated with human decision-making and behavioral considerations expounded earlier. This will leave us arguing at the start-line. On the other hand, if we ask AI to both govern the process for creating a common vision and to draw the map to get there, it does remind us of the AXIOM crew in Pixar’s Wall-E[i], where humans are reduced to inactive ‘blubbers’ under AI command while floating in space after having wrecked planet Earth. So what are we supposed to do?

We, Keynes’ Grandchildren

Left unchecked, AI delivering us free energy only serves to drive further inequality. Reverse engineering only succeeds insofar as we have a shared goal. But the way to achieve this shared goal is to outsource the vision to the AI. Does anything here remain that is remotely human and enjoyable if both prize and process is divorced from our own agency? And, besides, who says the human desire is to reduce work and make do anyway. Keynes’ essay “Economic possibilities for Our Grandchildren” serves as a pertinent illustration. Written in 1930, Keynes, the father of macroeconomics, predict that capitalism and continuous innovation together will solve, for good, the issue of scarcity. Quality of life will be 4-8 times higher, and working hours will be at around 15hrs/week. Keynes thus anticipates us slowing down - faced not so much with work but with a more intriguing challenge of finding meaning and purpose in life while deciding what to do with our freedom to pursue passions and happiness.

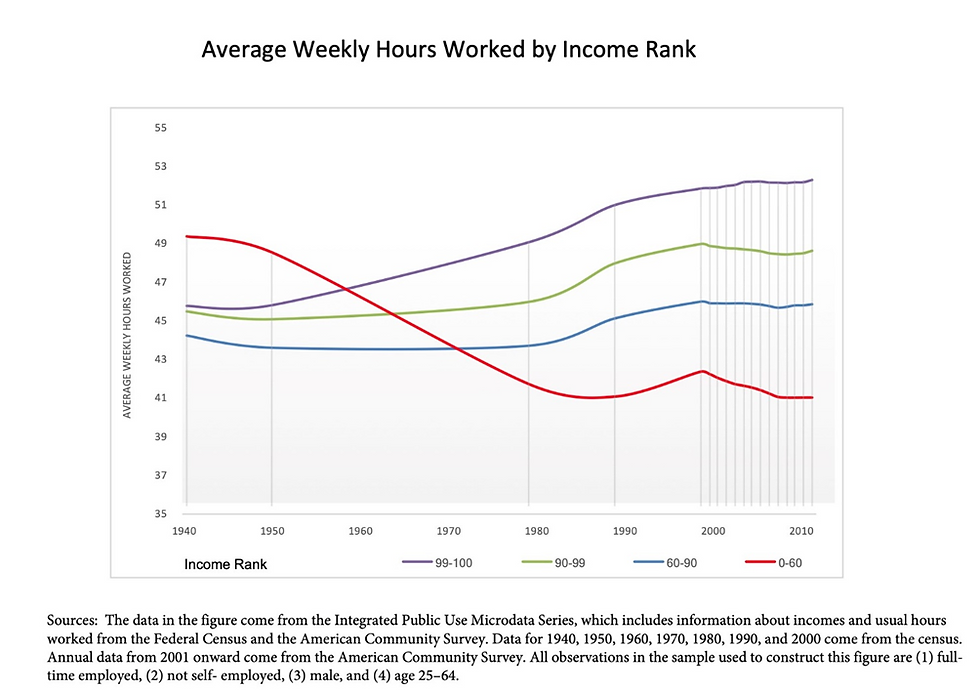

How did Keynes’ predictions pan out? He was wide off the mark. He overlooked the human psyche and/or had a severe blind-spot that was probably at least partially class-related. It turns out the middle class, which was about to inherit the world in the second half of the 20th century, did not share the value system of old Bloomsbury gentry. Today’s elite is, if anything, the antithesis of how Keynes imagined his grandchildren. There’s nothing vulgar about work. Daniel Markovits’ scholarship hammers home the irony, today’s elite on average works harder, in terms of brute hours, than they used to and harder than the middle class (Figure 2). This is while the extreme poverty rate is plummeting (Figure 3). It appears that we take wealth as motivation to pursue more wealth at an accelerating pace, not to work less and make art.

AI in Economic Climate Models

Maybe AI can help in terms of economic modeling? Is there a technocratic solution to climate change - wherein we allocate an optimal number of resources in a specifically determined way, and in that way achieve a theoretically defined optimal solution.

Economic models are built on a set of assumptions that simplify the complexities of the real world. These assumptions, while necessary for the model to function, can limit its accuracy and applicability. AI’s ability to process vast amounts of data and identify complex patterns can help relax these assumptions, leading to more accurate and nuanced models. AI has the potential to revolutionize economic modeling, offering new ways to analyze and predict economic phenomena. For instance, traditional economic models may assume that resources can be substituted indefinitely. This may not hold true in the face of finite resources. AI can get us out of the impasse by simulating multiple outcomes, each with different assumptions, to analyze the potential outcomes and identify the most likely and sustainable solutions. Perhaps this could debunk fundamentally incorrect assumptions? That would serve to avoid us chasing dead-end solutions which are dangerous to our time-constrained pursuit of NetZero.

But economics, including the subset of climate economics, sooner or later boil down to trade-offs, which are political in nature as opposed to computational. One of the key governing questions in any society is how to handle inequality. This is hard to give a technocratic answer to, and therefore perhaps impossible for an AI to help us resolve. Do we want to be free or do we want to be equal? Even an infinite dataset offers no conclusive evidence because there is no agreement or consensus on that.

Regarding climate models, the important thing when we try to model how we should reduce CO2 or to what extent we should intervene in aggregate production, often comes down to how much we value the future, the social discount rate. How much do we value our grandchildren’s happiness compared to our own happiness right now? Should it be a linear or a concave relationship? And that, again, is a philosophical and ethical question. To outsource the answer to the machine, we’d have to feed it a utility function. We’d have to somehow define our social preferences, which is an enormous political act.

How could we ever hope to reduce something as complex as individuals and all of humanity’s relationships to the future? But without being able to do so, it is problematic to believe that AI can solve the climate issue, from an economical modeling point of view.

AI and Psychology

The role of AI in climate change is about us, humans. It was our actions and decisions that led to the current climate crisis, and our actions and decisions will determine how we address it. Our perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors are shaped by a complex interplay of psychological factors. Understanding these factors can provide valuable insights into how we can effectively address climate change.

For instance, our tendency to prioritize immediate gains over long-term sustainability is a barrier to climate action. We face, and indeed have faced for a while, a multigenerational “delayed gratification” problem. It is as if we are collectively invited to take the Marshmallow test[ii], except instead of a child having to decide whether to eat the marshmallow now or wait for a bigger reward later, we are required to decide whether to continue using fossil fuels and emit greenhouse gasses now or reduce our consumption and emissions, when most of us won’t feel the benefits in our lifetime if we abandon fossil fuels. It is a very big ask. Is it too big to move the needle?

Generally, our human instinct is to resist change and our attachment to established norms and practices can hinder our progress towards sustainability. It is the evolutionary force of memory bias that keeps us clinging on to suboptimal behaviors even when faced with overwhelming evidence. Only when the cost of inaction greatly surpasses the status quo’s value and adaptation is critical to survival, will change really happen. Are we at this tipping point yet and can AI help us increase motivation and reduce the compounding hurt that comes from delayed action?

AI has the potential to compensate for some of the limitations deeply embedded in human psychology. By providing us with data-driven insights and objective analyses, AI can help us make informed and sustainable decisions. The effectiveness of AI in this regard is contingent on our willingness to accept and act on these insights. Moreover, the use of AI raises ethical and philosophical questions. To what extent can we delegate our decision-making to AI? What are the implications of relying on AI to guide our actions and behaviors? The advent of AI also raises questions about the future evolution of human psychology. As we increasingly interact with and rely on AI, how will our psychology adapt? Will we become more rational and data-driven in our decision-making, or will we become more dependent on AI to make decisions for us? What biases are built into the model?

What AI can and what AI cannot do

In the Large Language Models (LLMs), we appear to have put into the world a new form of intelligence, which scores extremely high on processing a lot of knowledge with immaculate and infinite recall. But this subset of AI currently does not appear to have any fundamentally creative ability, or that is, for now it is a synthesis of previous creativity[1]. For now, AI as “personified” by LLMs appears to have clear limits, it extrapolates. It is our own collective, human, intelligence staring back at us. The LLM kind of AI is helpful and will enhance our productivity, but maybe we shouldn’t expect too much. The saying goes “what got us here, will not take us where we need to go”.

Using AI, we want to play to its strengths. When applied as Alphafold, with its ability to predict complex three-dimensional structures accurately, AI computing power does something that no human being could ever hope to do. Here processing power leads to actual discovery, something much closer to what we normally associate with creativity. In the realm of environmental research, we can expect advances in discovery within materials, proteins and crops. Computational power allows nuclear simulations that drives down costs and reduces time-to-market for next generation power plants. This ability will has the potential to frog leap us away from the doom and gloom from the climate crisis.

Resource Optimization

AI can optimize resources for us. There are hidden clues in analyzing patterns of resource consumption and production, which we can use to remove inefficiencies and propose solutions. This could be particularly useful in renewable energy, where optimizing resource use can significantly enhance sustainability. This is already happening within geospatial planning for instance, but what about resources broadly – like the metals and rare earths required to make the wheels of the vision turn. We think there are huge opportunities here - geological data, seismic data, satellite imagery will likely allow for more economical and environmentally friendly extractions.

AI and Inequality

Looking at what is happening in the world today, and how we’ve presently chosen to distribute resources, it seems that there is nothing, politically, to suggest that we have the means or intentions to deal meaningfully with inequality. If AI accelerates productivity and hence wealth, this quickly become an even bigger problem. A key question, insofar as AI is productivity-enhancing, is: will the spoils go to wage earners or the owners of the algorithm?

When it comes to how AI technology will be owned, current trajectory suggest that they will likely be controlled in some oligopoly by Open AI, Microsoft, and Google and Deepmind and maybe Amazon. There’s an alternative scenario where the AI models are open source via Facebook. What should we think of this? Does this merely accelerate the discussions we’ve been having about surveillance capitalism? Power appears to reside in and with the incumbents whose free cash flow is right now being invested at unprecedented levels. AI relies on computing power, and a war chest of cash seems to stack the odds in favour of today's tech giants. If we accept the collective wisdom of the market, this is indeed what’s taking place right now. The growth of the mega-caps is far outpacing the broader growth in the stock markets.

To what extent does legislation wish, or indeed manage, to rein in the power of tech giants to out-invest everybody else in advanced chips and their applications? To what extent can legislators reconcile national, regional, and global interests?

We think AI, best case, can democratize wealth distribution, sort of what decentralized finance is trying to be for finance regulation – an enabler of equal opportunity and wealth. The worst case would be the opposite – an extreme acceleration of the wealth gap.

AI and Externalities

It’s uncontroversial that economic growth often comes with negative externalities. However, there’s nothing preventing us from accounting for these. Externalities are when the private transaction between two parties (e.g. our filling up the tank at the local Shell petrol station) comes with a social cost (damage to the air quality, CO2 emission, likelihood of me running into a pedestrian etc.). If we can price this cost reasonably accurately, we can still, by way of taxes or quotas, arrive at a solution that balances our utility from driving with society’s disutility from us out there on the road. The problem is a) can we price the damage? b) can we agree on implementing taxes/quotas when the external cost seeps across national boundaries/jurisdictions?

AI has arrived with its own set of externalities that will only become gradually apparent to us. Because they are happening in real time, we can expect to have a hard time pricing them correctly. Because AI is released into the world on a global scale, it is far from obvious who should own the jurisdiction. So, if Alphafold-equivalent technology manages to solve 90% of the technical problem connected to climate change, but AI at the same time enables disinformation such that our political landscape gets even more fragmented, this could well lead to paralysis rather than action. We don’t know in advance which force is more powerful, the damage to our political institutions or the gains to our technological tool-kit.

Key takeaways for AI and the Green Transition

Key take-away 1: We need to disassociate political questions from computational questions.

The binding constraint is perhaps the extent to which the latter are constrained by the former.

Key take-away 2: Long term global problems are incompatible with national democracies, even when aided by AI.

In terms of AI being the ultimate technocrat, allowing for a data-driven economic policy, we run into the familiar problem of climate change happening in the long run. Any “optimal solution” derived by way of AI modeling/simulation is likely to contain a planning cycle which far exceeds the time frames suited to democratic governance. There is a clear disconnect between problem-time-horizons (long) and political-time-horizons (4-5 year) that negates an AI defined solution. There’s a clear disconnect between problem scope (global) and democratic scope (national).

Key take-away 3: The future does not always equal the past

Regarding the impetus for urgent decision-making, we can never know for certain if our current economic models/analyses are correct. The Malthusian model of the world pre-Industrial Revolution 1.0 suggested that increased population would only accentuate human suffering and turned out woefully wrong. The demographic transition and continued technological growth fundamentally changed the economic laws of society. Today one side argues that technology will save us. The other says, no, growth only appears to have a positive sign because we are not properly accounting for the negative externalities.

Key take-away 4: Our psychology will likely be determinative

AI can help us use resources efficiently. It will likely help us access more resources at reduced prices. But to what extent will this merely increase consumption? Can we ever truly settle the debate between sustainable growth and degrowth? Balancing the benefits of resource optimization with the need for conservation is a significant challenge. Then there is the Marshmallow trade-off, balancing immediate gratification with long-term sustainability. Ethically and philosophically, can we delegate our decision-making to AI? What are the implications – it’s a surrender experiment if we do it. On the other hand, we won’t know till we try, and if we try, perhaps we can’t go back.

Conclusion

We have attempted to cover some potential applications of AI in addressing climate change, implications for economic models, the trade-offs involved, and philosophical questions. We’ve also taken stock of human psychology. We predict the journey is just beginning. Our exploration has underscored the pivotal role of the human factor. While AI offers exciting possibilities, it is ultimately up to us. We must be willing to change our behaviors and make difficult decisions as a collective.

If we change that precondition, we are betting that AI is better at both analyzing, engineering, and governing our future trajectory. That is a scary thought. AI is a powerful tool, but it is not a panacea. The role of AI in addressing climate change is a mirror reflecting our own strengths and weaknesses, our hopes and fears. It challenges us to use our intelligence, both artificial and human, to create a better, more sustainable world. As we continue this journey, we must remember that the future is not something that happens to us, but something we create.

In Appendix 1 on the next page is a SWOT analysis on the AI and the Climate Crisis interplay. Each element can be unbundled and applied into industry. If your organization needs to leverage our insights, data, and industry access for your operations, connect with us.

Thanks for reading and learning with us,

Jesper Bork Petersen & Mads Prange Kristiansen

Comments